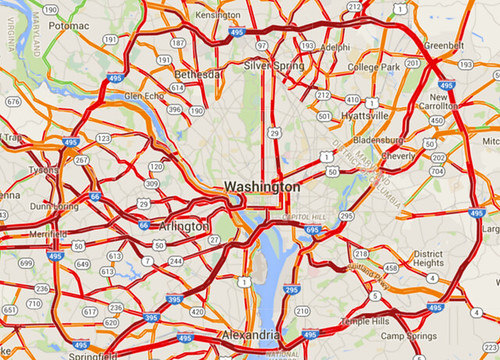

A lot of people had awful commutes last night, thanks to snow. And a lot of people had fine ones. One explanation for the difference: Suburban roads are far more susceptible to catastrophic breakdown than urban street grids.

Traffic congestion on snow night. Image from Google.

Snow storms like last night’s highlight how easy it is to completely shut down suburban-style transportation systems. And conversely, how comparatively resilient are more urban systems.

Cities beat suburban areas on snow resiliency in two big ways: Multimodalism and network connectivity.

First and foremost, with transit, walking, and biking more convenient options, cities are simply much less reliant on having clear roads. Metrorail worked like a dream yesterday, and pedestrians had a lovely commute.

It simply didn’t matter how bad the roads got for a significant percentage of DC’s travelers, because they simply weren’t on the roads while they traveled.

Don’t put all your eggs in one basket

But that’s not all. Even for car drivers, urban street grids are more resilient than road systems focused around large highways, because of how they’re laid out.

The great thing about interconnected grids is that if one street becomes blocked, there’s another perfectly good street one block over. And another one block down.

If a wrecked car or fallen tree or whatever blocks the street you’re on, you just take a different street. There might be some additional turns involved; it might not be quite as direct. But for the most part 28th Street isn’t all the different from 29th Street.

Contrast that with suburban-style systems where all traffic in a particular area funnels onto one big highway. If that one highway becomes impassible, everyone in the area is stuck. Or, at best, they have to drive miles out of their way to find the next big highway.

This illustration shows how that works. If the “Collector Road” gets jammed, people in the top half of the image can still move around. People on the bottom half can’t.

Suburban-style roads vs urban street grid. Image from USDOT.

That’s part of what happened last night. There were a lot of crashes. If they happened on arterial highways with no parallel roads, which a lot of them did, that road would succumb to gridlock.

Urban places aren’t immune, but they’re better off

To be sure, this storm was bad for roads all over the region.

Streets in Northwest DC were just as dangerous as those elsewhere, and DC’s plowing response was bad. And buses were every bit as stuck in it as cars.

But there’s no doubt that people who could travel via Metro or foot had a much better time, and there’s no doubt that drivers who could use parallel streets were able to bypass some of the congestion on arterials.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

January 21st, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: environment, master planning, roads/cars, transportation