There is much confusion over what separates streetcars from light rail. That’s because there’s no single easy way to tell, and many systems are hybrids. To tell the difference, one has to simultaneously look at the tracks, train vehicles, and stations.

|

|

San Francisco’s Muni Metro runs both in a dedicated subway and on the street in mixed traffic.

Is it a streetcar or light rail system?

Photos by Matt Johnson and SFbay on Flickr. |

It’s hard to tell the difference because streetcars and light rail are really the same technology, but with different operating characteristics that serve different types of trips.

The difference, in a nutshell

Theoretically light rail is a streetcar that, like a subway or el, goes faster in order to serve trips over a longer distance. But what does that mean in practice?

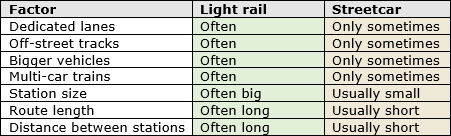

There are several features of tracks, vehicles, and stations that both streetcars and light rail sometimes have, but which are generally more common on light rail. Thus, although there’s no single separating test that can tell the two apart with 100% accuracy, it’s usually possible to tell the difference by looking at several factors simultaneously.

Let’s look at each of those factors, one by one.

Lanes and tracks

It’s a common misconception that streetcars always run in mixed traffic with cars, while light rail has its own dedicated track space. That’s often true, and it’s such a convenient and easy-to-understand definition that I’ve been guilty of using it myself. But it’s wrong.

There are too many exceptions to that rule to rely on it completely. Sometimes (though rarely) light rail lines run in mixed-traffic, and there are plenty of streetcars with their own right-of-way. Some streetcars even have subways.

Compare Sacramento’s mixed-traffic light rail with Philadelphia’s streetcar subway, for instance:

|

|

Left: Sacramento light rail in mixed traffic. Photo by Flastic on Wikipedia.

Right: Philadelphia streetcar in a subway. Photo by John Smatlak via Flickr. |

In fact, practically every mixed-traffic streetcar has at least a short section of dedicated track. That’s true in Atlanta, Seattle, Tucson, even DC. Those streetcar lines don’t suddenly become “light rail” for one block just because they have a dedicated lane somewhere. It’s just not that simple.

And some streetcars have long stretches with dedicated lanes. Toronto’s massive streetcar network has several dedicated transitways, and DC is planning one on K Street.

|

|

Left: K Street transitway. Image from DC Streetcar.

Right: Toronto’s Saint Clair transitway. Photo by Sean Marshall via Flickr. |

There are too many streetcars with dedicated lanes for that to be a reliable indicator on its own. Too many lines that mix dedicated and non-dedicated sections. Certainly it’s an important data point; certainly it’s one factor that can help tell the difference. But it’s not enough.

An even simpler definition might be to call anything with tracks in the street a streetcar, and anything with tracks elsewhere light rail.

But that’s not reliable either, as Portland and New Orleans illustrate:

|

|

Left: Portland light rail. Photo by BeyondDC.

Right: New Orleans streetcar. Photo by karmacamilleeon via Flickr. |

Salt Lake City muddies the water still further. Its “light rail” mostly runs in the street, while its “streetcar” runs in an old freight train right of way, almost completely off-street.

|

|

Left: Salt Lake City light rail. Photo by VXLA on Flickr.

Right: Salt Lake City streetcar. Photo by Paul Kimo McGregor on Flickr. |

Vehicles and trains

If tracks on their own aren’t enough to tell the difference, what about vehicles?

It’s tempting to think of streetcars as “lighter” light rail, which implies smaller vehicles. Sometimes that’s true; a single DC streetcar is 66 feet long, compared to a single Norfolk light rail car, which is over 90 feet long.

But not all streetcars are short. Toronto’s newest streetcars are 99 feet long.

Toronto streetcar. Photo by Swire on Flickr.

In fact, many light rail and streetcar lines use the exact same vehicles. For example, Tacoma calls its Link line light rail, and uses the same train model as streetcars in Portland, DC, and Seattle, while Atlanta’s streetcar uses the same train model as light rail in San Diego, Norfolk, and Charlotte. And Salt Lake City uses the same train model for both its streetcar and light rail services.

|

|

Left: Tacoma light rail. Photo by Marcel Marchon via Flickr.

Right: Portland streetcar. Photo by Matt Johnson on Flickr. |

|

|

Left: San Diego light rail. Photo by BeyondDC.

Right: Atlanta streetcar. Photo by Matt Johnson via Flickr. |

And although streetcars often run as single railcars while light rail often runs with trains made up of multiple railcars, there are exceptions to that too.

San Francisco’s Muni Metro and Boston’s Green Line definitely blur the line between streetcar & light rail, perhaps more than any other systems in North America. Some might hesitate to call them streetcars. But they both run trains in mixed-traffic with cars, and some of those trains have multiple railcars.

Meanwhile, many light rail systems frequently run single-car trains, especially during off-peak hours.

|

|

Left: Norfolk light rail with a single car. Photo by BeyondDC.

Right: San Francisco streetcar with two cars. Photo by Stephen Rees via Flickr. |

Stations offer some help, but no guarantee

Light rail typically has bigger stations, while streetcars typically have smaller ones. A big station can sometimes be a good clue that you’re likely dealing with light rail.

For example, look at Charlotte and Portland:

|

|

Left: Charlotte light rail. Photo by BeyondDC.

Right: Portland streetcar. Photo by BeyondDC. |

But that’s only a general guideline, not a hard rule. Just like tracks and vehicles, there are many exceptions. Light rail often has small stops, and streetcar stations can sometimes get pretty big (especially when they’re in a subway).

This light rail stop in Norfolk is smaller than this streetcar stop in Philadelphia, for example:

|

|

Left: Norfolk light rail. Photo by BeyondDC.

Right: Philadelphia streetcar. Photo by BeyondDC. |

Stop spacing and route length

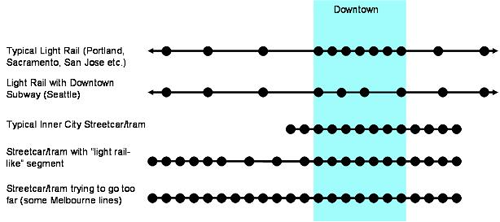

Probably the most reliable way to tell streetcars apart from light rail is to look at where the stations are located. Light rail lines typically have stops further apart from each other, on lines covering a longer distance.

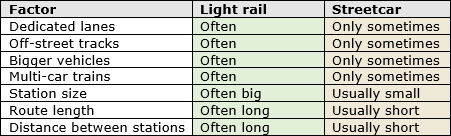

This chart explains the difference:

Image from Jarrett Walker.

This is the definition transit expert Jarrett Walker favors, and if you have to pick just one or two factors to consider, stop spacing and route length are the best.

But even this is no sure way to categorize all lines as either streetcars or light rail. It might be easy to tell the difference between something with stops one block apart (theoretically streetcar) versus stops two miles apart (theoretically light rail), but what if the stops are 1/4 mile apart? Or what if the gaps aren’t consistent? There’s no clear place to draw the line.

Furthermore, Walker’s graphic itself illustrates exceptions to the rule. The top line shows a light rail route with stops close together downtown, the third line shows a streetcar with some sections that have far-apart stations, and the fourth line shows a very long streetcar.

There are certainly plenty of real-life examples of those exceptions. Before Arlington, VA cancelled its Columbia Pike streetcar, DC and Arlington were considering linking their streetcars with a bridge over the Potomac River. Had that happened, there might have been a mile-and-a-half between stops.

Certainly station spacing and route length provide a convenient general rule, but only that. There’s no hard boundary where everything to one side is streetcar, and everything to the other is light rail.

To really know the difference, look at everything

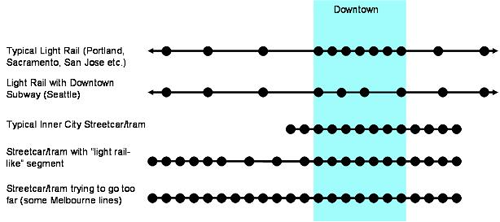

There are seven factors that light rail usually has, but that streetcars only sometimes share: Dedicated lanes, off-street tracks, bigger vehicles, multi-car trains, longer routes, bigger stations, and long distances between stations.

No single one of them provides a foolproof litmus test, because sometimes streetcars have each of them, and sometimes light rail doesn’t. But if you look at all seven together and determine which direction the majority of a line’s characteristics point, over the majority of its route, then you can usually sort most lines into one category or the other.

For example, DC’s H Street line fits neatly into the streetcar category, because it runs in the street almost totally in mixed traffic, with small vehicles on single-car trains, along a short route that has frequent, small stations. Even if DDOT builds the K Street transitway and a dedicated-lane streetcar on Georgia Avenue, the majority of the seven factors will still point to streetcar.

On the other end of the spectrum, Seattle’s Central route is squarely light rail. It has a dedicated right-of-way that’s often off-street, uses large 95 foot-long vehicles that are usually coupled into multi-car trains, along a long route with infrequent stations.

|

|

Left: Seattle light rail. Photo by Atomic Taco on Flickr.

Right: DC streetcar. Photo by BeyondDC. |

But even then not every system is crystal clear. San Francisco’s Muni Metro, Philadelphia and Boston’s Green Lines, and Pittsburgh’s T, for example, all have some segments that look like classic streetcars, but also some segments that look like classic light rail. These networks defy any characterization, except as hybrids.

It’s a feature, not a bug

The fact that it’s hard to tell the difference is precisely why so many cities are building light rail / streetcar lines. The technology is flexible to whatever service characteristics a city might need.

You can use it to build a regional subway like Seattle, or you can use it for a short neighborhood circulator like DC’s H Street, or anything in-between. And perhaps even more importantly, you can use it to mix and match multiple characteristics on the same line, without forcing riders to transfer.

That’s why many of the most successful light rail / streetcar systems are the hardest ones to categorize as either / or. They match the infrastructure investment to the needs of the corridor, on a case-by-case basis, and thus have some sections that look like light rail, and others that look like streetcar.

That’s not muddied. That’s smart. That’s matching the investment to the need, which is after all more important than a line’s name.

Cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington.

Cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.5 out of 5 based on 247 user reviews.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.