|

Special Features

Image Libraries

|

|

Blog

Mayor Bowser's latest DC budget proposal includes $165 million to replace the Hopscotch Bridge. Once a new bridge is open, an eyesore will become a prime public space, and long-awaited expansions of Union Station and DC Streetcar can finally happen.

Rendering of the new Hopscotch Bridge, surrounded by new development behind Union Station. Image by Akridge.

Today, Hopscotch Bridge carries H Street over the railroad tracks behind Union Station. In order to make room for trains to pass below, the bridge rises high above H Street's normal elevation. With solid walls and the Union Station parking garage on either side, the bridge is a three block long stretch of desolation, amid an otherwise vibrant part of the city.

Replacing the bridge will change that.

Existing Hopscotch Bridge. Image by Bossi licensed under Creative Commons.

A new bridge, designed specifically to accommodate buildings on either side, will make it possible to develop the air rights above Union Station's railyard, and to replace the parking garage with a new train hall. What was desolate will become a major new public space, with landmark architecture, a mix of uses, and a more open, European-style train hall.

That development is called Burnham Place. It's a very ambitious plan.

Proposed H Street entrance to Union Station, as part of Burnham Place. Image by Akridge.

Streetcar can go downtown

Building a new Hopscotch Bridge also opens to door to finally extending the H Street Streetcar to downtown Washington and Georgetown. The streetcar doesn't specifically need a new bridge, but timing is an issue. DDOT doesn't want to extend the streetcar now only to rip up tracks and suspend service in a couple of years when the bridge is torn down and replaced anyway.

As it is, tearing down and replacing the existing bridge will mean temporarily removing the streetcar stop atop the bridge. That's bad enough, but it would be a much worse situation with streetcars running downtown.

When it runs downtown, DC Streetcar will have a dedicated transitway. Image by DDOT.

Budget details

Mayor Bowser's proposal would fund $165 million in 2019 and 2020. The DC Council will have to approve the budget before it becomes law. Even if it does, another $40 million would still be needed before construction could begin. That money would either come from other sources, or a future year's budget.

Once funding is fully in place and DDOT completes the final design, construction should take about two years.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 5 out of 5 based on 241 user reviews.

April 4th, 2017 | Permalink

Tags: development, funding, government, master planning, roads/cars, streetcar, transportation

Here we are. Donald Trump is America's president. The largest protest in American history greeted his first day. Welcome to Washington and the USA in 2017.

Saturday’s Women’s March. Image from Mobilus In Mobili on Flickr.

Our weekend was momentous

Two days, two gigantic events.

As inaugurations go, Friday's was noticably small. But even a small inauguration is big enough to change the tone of city life.

Security fences partitioned blocks of downtown, and an army of police forces dominated the streets. Many locals stayed away to avoid the logistical and emotional headaches. Parts of the city became eerily dead, while others burst with unusual life, as Trump supporters descended to hotels and tourist areas around the White House.

Washington became a foreign city, its own residents outsiders to a security and tourist project to which we didn't belong, nor feel healthy within.

Security barriers in an empty downtown.

During the inauguration itself, Metro ran smoothly. Trump presented a bleak picture of America. Protests raged, mostly peacefully, sometimes not. GGWash's own David Whitehead proved that deescalation works.

The new administration erased climate change from presidential priorities, and disciplined the National Park Service for reporting meager crowds. Joe Biden took Acela home to Delaware.

We went to bed, unsure the country we would wake to find.

And then, on Saturday, three times more people attended the Women's March than Friday's inauguration. Nationwide, at least three million took to the streets.

There was grief and humor and defiance. Mayor Bowser chanted "Leave us alone!, " DC police donned pink hats, and Metro had its second busiest day ever.

In contrast to Friday, Saturday's Washington felt more ours than ever. The city became strangely joyous, as march-goers spread over downtown and the National Mall to reclaim our public spaces, replacing the inauguration's fenced-off security apparatus with revelry lasting well into the evening.

We went to bed with renewed determination.

Image from Andrew Aliferis on Flickr.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump's press secretary brazenly lied, and his counselor hoped to replace the truth with "alternative facts" intended to sow uncertainty and estrange the media.

The policy fights are just beginning

Trump may be the most urban president in history, but his party and his base are vehemently anti-urban. Administration policy seems to be largely under the purview of Vice President Pence, whose small town Indiana roots are decidedly not urban.

They plan dramatic cuts to many federal departments, including the Department of Transportation, where multimodal infrastructure spending will likely decline in favor of tax breaks for construction firms. The Environmental Protection Agency is likely to be gutted, enabling a new round of urban pollution and ending the fight against climate change. HUD raised prices for first-time homebuyers within an hour of Trump's swearing-in. The Department of Justice will no longer pressure police departments over civil rights.

What will the EPA look like in four years? Image from Paul Fagan on Flickr.

Locally, such massive cuts and a proposal to strip benefits from government employees could throw Washington's economy into recession, as jobs bleed out of the city. Or security and military spending could lead to a new boom. Either way, Congress' small government Republicans will override local decision-making in DC.

Nationally, the right is emboldened, while the left is beginning to act like a true opposition.

So, here we are. Donald Trump is America's president. The future of our city and our country is uncertain. We face colossal challenges. But GGWash's mission and values are still worthwhile, and our community is as strong as ever. We'll be here.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.9 out of 5 based on 300 user reviews.

January 23rd, 2017 | Permalink

Tags: economy, environment, events, government, in general, metrorail, The New America, transportation

Metro has a trust problem that’s impeding the agency’s ability to fix its decaying rail system. Riders and city officials don’t believe the agency’s proposed permanent cuts are necessary. To solve this one way or another, Metro must regain rider trust by precisely reporting exactly what its rebuilding needs are, and whether efforts thus far have been successful.

This series of seven tweets explains why this problem persists, and how being legitimately transparent can only help WMATA achieve its goals.

WMATA has tried to explain its maintenance plans, and has occasionally reported on progress, but there’s no single resource available to riders all the time that compiles all Metro’s needs, both SafeTrack and non-SafeTrack, and reports on progress in detail.

For example, how many feet of track must be rebuilt before Metro reaches a state of good repair? Out of that, how many feet has WMATA successfully rebuilt to date? How many feet were fixed in July?

That’s the kind of information that will help decision makers and the public understand what WMATA needs, and thus support informed decision-making.

If possible, still more detail would be even better. How many rail ties have been fixed, out of how many that need to be? How many insulators? How many escalators and elevators? That level of detail may not always be possible to report (WMATA may not know the full needs until they start doing work), but after so many years of frustration, this is the kind of information the public requires to feel comfortable with Metro’s progress. The data should be specific and be listed for each station or between stations, if possible, so passengers can know exactly where work still needs to be done

In Chicago, ‘L’ riders can see a detailed map of slow zones in the system, and New York’s MTA runs video explainers about system problems. These are good examples worth emulating, but WMATA must go further.

If Metro officials hope to get buy-in for extreme measures like permanently cutting late night service, it’s reasonable for the public to demand extreme explanations, and reassurance that sacrifice will result in improvements. Without more frequent and more candid communication about progress, trust in WMATA will continue to erode, political support for sacrifices will be hard to obtain, and the spiral of decaying service will likely deepen.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.6 out of 5 based on 240 user reviews.

September 18th, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: government, metrorail, proposal, transportation

This amazing map from 1861 shows a federal government proposal to redraw the borders of Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, and DC. The reason: To spite Virginia for the Civil War and better-protect the capital from attack.

1861 proposal to redraw the borders of Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, and DC. Image by Harper’s Weekly.

The map is from an 1861 edition of Harper’s Weekly, and is based on an idea from federal Secretary of War Simon Cameron. Here’s how Harper’s Weekly described the idea:

This arrangement would reduce the size of the State of Virginia at least one-half, leaving the name of Virginia to that part only which is now mainly loyal.

The disloyal section, comprising all the great cities of Virginia—Richmond, Norfolk, Fredericksburg, Lynchburg, etc.—and all the sea-coast, would be annexed to Maryland, while Delaware would rise, by spreading over the whole peninsula between the Chesapeake and the ocean, to be a State of considerable magnitude.

Under this reconstruction Maryland would become one of the three great States of the Union. We need hardly direct attention to the clause in the Secretary’s report which hints that emancipation in Maryland must be the price paid for this acquisition of territory.

Alexandria and Arlington would have returned to DC, which would have remained independent of any state.

When Cameron came up with his idea, the Civil War was less than a year old. The western more rural portions of Virginia had hoped to remain in the Union, while the more urban eastern portions had voted overwhelmingly to secede. In theory, this proposal therefore would have accomplished several goals. It would have:

1. Separated off the loyalist western parts of Virginia, allowing them to be reintroduced to the Union as a northern state.

2. Punished eastern Virginia, the intellectual and economic heart of the Confederacy, by taking away its independence as a state.

3. Rewarded Maryland and Delaware for remaining in the Union.

4. Protected Washington from having a hostile territory directly across the Potomac.

It’s not as crazy as it seems

In 1861, as Cameron was making this proposal, West Virginia was already in the process of splitting off from Virginia to become its own state. How exactly to draw its borders and what to call it was a perfectly reasonable question.

The most doubtful part of this idea is the notion that new-and-bigger Maryland would be a safe northern state. Although Maryland never seceded, it was a slave state and its loyalty to the Union during the Civil War was tenuous at best.

Adding the wealthy and populous parts of Virginia to Maryland seems more likely to have drawn Maryland towards the south than vice versa. Presumably that’s why the deal would have required Maryland to free its slaves.

Of course as we all know, this proposal didn’t work out. West Virginia’s boundaries and name became official in 1863 when it was admitted to the Union as its own state, and Virginia was itself readmitted in 1870 following four brutal years of Civil War.

But it’s interesting to look back and see what could have happened, had history turned out just a little bit differently.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 5 out of 5 based on 276 user reviews.

March 3rd, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: government, history

In 1912 Baltimore’s city leaders hoped to annex this large chunk of Baltimore County. Had that happened, the city limits would have extended from just shy of downtown Towson to just shy of Ellicott City.

Image from the State of Maryland.

Baltimore annexed big chunks of land in three successive waves: One in 1817 that took the city as far as North Avenue, a second in 1888 up to about 40th Street, and a third in the early years of the 20th Century.

Like other US cities, Baltimore was expanding rapidly in the early 20th Century amidst a wave of streetcar-induced sprawl. Suburban areas lacked city services like sewers, parks, and police, so central cities often annexed surrounding land.

By about 1910, Baltimore was ready for another round of annexation. Exactly how much land the city should annex became a major hot-button issue of the day, with proposals ranging from no expansion to the aggressive, far-ranging one pictured above.

In 1918 a compromise plan eventually won out, settling Baltimore’s boundaries at their current extents.

By the time America’s post-World War II suburbanization boom happened, the national mood had shifted against central cities. A 1948 amendment to Maryland’s state constitution outlawed any further expansion of Baltimore city, and thus the borders haven’t changed since.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.7 out of 5 based on 242 user reviews.

March 3rd, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: government, history, maps

There are more than 20 separate bus agencies in the Washington area. Why not run them all as part of WMATA? Some run outside WMATA’s geography, but the bigger reason is money: It costs less to run a local bus than a WMATA bus, translating to better service for less money on local lines.

With a few exceptions, essentially every county-level local government in the Washington region runs its own bus system, on top of WMATA’s Metrobus. DC has Circulator, Montgomery County has Ride-On, Alexandria has DASH, etc ad nauseam. There are more than 20 in the region, not even including myriad private commuter buses, destination-specific shuttles, and app-based startups.

Our region is a smorgasbord of overlaying transit networks, with little in common except, thankfully, the Smartrip card.

Why?

Three reasons, but mostly it’s all about money

Some of the non-WMATA bus systems can’t be part of Metro simply because buses go to places that aren’t part of the WMATA geography. Since Prince William County is outside WMATA’s service area, Prince William County needs its own system. Thus, OmniRide is born. Hypothetically WMATA could expand its boundaries, but at some point 20 or 40 or 60 miles out from DC, that stops making sense.

Another reason for the transit hodgepodge is control. Locals obviously have more direct control over local systems. That’s an incentive to manage buses close to home.

But the biggest reason is money. Specifically, operating costs.

To calculate how much it costs to operate a bus line, transit agencies use a formula called “cost per revenue hour.” That means, simply, how much it costs to keep a bus in service and carrying passengers for one hour. It includes the cost of the driver’s salary, fuel for the bus, and other back-end administrative costs.

Here are the costs per hour for some of the DC-region’s bus systems, according to VDOT:

- WMATA Metrobus: $142/hour

- Fairfax County Connector: $104/hour

- OmniRide: $133/hour

- Arlington County ART: $72/hour

Not only is WMATA the highest, it’s much higher than other local buses like Fairfax Connector and ART. OmniRide is nearly as high because long-distance commuter buses are generally more expensive to operate than local lines, but even it’s less than Metrobus.

This means the local systems can either run the same quality service as WMATA for less cost, or they can run more buses more often for the same cost.

At the extreme end of the scale, Arlington can run 2 ART buses for every 1 Metrobus, and spend the same amount of money.

In those terms, it’s no wonder counties are increasingly pumping more money into local buses. Where the difference is extreme, like in Arlington, officials are channeling the vast majority growth into local buses instead of WMATA ones, and even converting Metrobus lines to local lines.

Why is Metrobus so expensive to run?

Partly, Metrobus is expensive because longer bus lines are more expensive to run than shorter ones, so locals can siphon off the short intra-jurisdiction lines for themselves and leave the longer multi-jurisdiction ones to WMATA.

Another reason is labor. WMATA has a strong union, which drives up wages. The local systems have unions too, but they’re smaller and balkanized, and thus have less leverage.

Finally, a major part of the difference is simply accounting. WMATA’s operating figures include back-end administrative costs like the WMATA police force, plus capital costs like new Metro bus yards, whereas local services don’t count those costs as part of transit operating.

Montgomery County has a police department of course, and bus planners, and its own bus yards, but they’re funded separately and thus not included in Ride-On’s operating costs.

So part of the difference is real and part is imaginary. It doesn’t actually cost twice as much to run a Metrobus as an ART bus. But for local transit officials trying to put out the best service they can under constant budget constraints, all the differences matter.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.4 out of 5 based on 199 user reviews.

February 22nd, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: bus, government, transportation

Maryland Governor Larry Hogan announced today the state will build the Purple Line.

Hogan announced his decision to build the light rail line at a press conference at 2:30 this afternoon.

To reduce costs, trains on the Purple Line will come every seven and half minutes rather than every six. The state will not change the alignment, nor the number or location of stations.

The Purple Line has been on the books for decades, and enjoys wide support in Maryland’s urban and suburban communities surrounding DC. It was primed to begin construction this year, but Governor Hogan has been threatening to cut it since entering office.

Our neighbors in Baltimore are not so lucky. At the same presser, Hogan announced the Baltimore Red Line will not move forward as currently conceived.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 5 out of 5 based on 224 user reviews.

June 25th, 2015 | Permalink

Tags: events, government, lightrail, transportation

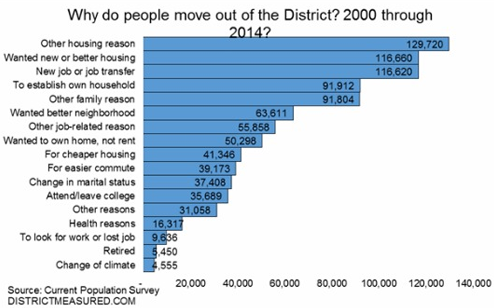

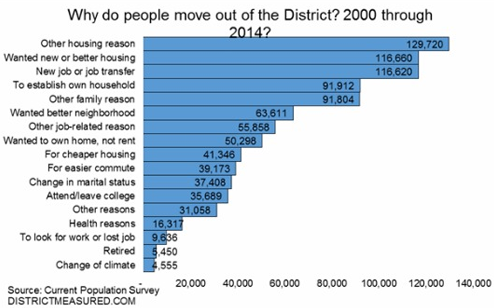

DC’s population is rising overall. But amid that rise, hundreds of thousands of people have come or gone since the year 2000. Among those who have left, inadequate housing is by far the biggest single reason.

Image from the DC Office of Revenue Analysis.

According to survey data summarized in this report from the DC Office of Revenue Analysis, 937, 115 people have moved out of DC since the year 2000. 36% of them, 338, 000, cite a housing-related category as the reason why.

Some respondents say directly they needed cheaper housing. Others say they wanted newer housing, or better housing, or to own instead of rent. But the common denominator is that DC’s housing stock is inadequate, and that inadequacy is stifling the District’s population growth, as thousands who’d otherwise prefer to stay move away.

Every time some government agency restricts the housing market’s ability to meet DC’s tremendous demand, they make this problem worse. Every time the zoning commission downzones rowhouse neighborhoods, or every time a review board lowers a proposed building’s height, DC’s housing market becomes a little bit worse than necessary.

Over time as each restriction builds on the last, competition for the limited housing that’s available rises, prices shoot up, and the city’s less affluent populations are squeezed out.

It’s true that DC can never be all things to all people. For example, DC will never be able to supply as many large lot subdivisions as upper Montgomery County. But many types of housing that DC can absolutely supply are being unnaturally and unnecessarily restricted.

It’s a horrible situation.

What about schools?

DC’s inadequate schools are without a doubt also a major reason some people leave the District. According to Yesim Sayin Taylor of the Office of Revenue Analysis, we don’t know how many residents have left because of schools because the survey, which wasn’t designed specifically for DC, didn’t ask that question.

Presumably respondents who left because of schools cited something more general like “other family reason” or “wanted better neighborhood.”

Cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington. Cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.7 out of 5 based on 251 user reviews.

June 12th, 2015 | Permalink

Tags: demographics, development, economy, government, law, preservation

In case anyone is wondering, as an Arlington employee it’s not prudent for me to blog about the Arlington County board’s decision to cancel the Columbia Pike and Crystal City streetcars.

Greater Greater Washington has excellent coverage of the issue, though.

Average Rating: 4.4 out of 5 based on 204 user reviews.

November 21st, 2014 | Permalink

Tags: events, government, streetcar, transportation

|

Maryland Governor’s Mansion. Image from the Boston Public Library on Flickr. |

Despite years of work and broad community support to build the Purple Line, Maryland’s new Republican governor-elect may kill the project. Does Maryland’s heavily centralized state-level planning make it particularly susceptible to shifts like this one?

Most US states delegate transit planning to regional or municipal agencies, rather than doing it at the state level. Maryland is unusual. It’s geographically small and dominated by urban areas, and it has a history of governors interested in planning. So the state handles much more planning than usual, especially for transit.

That can be a mixed blessing.

When things go well, it means Maryland directs many more resources to transit than most other states. But it also means transit projects in Maryland are inherently more vulnerable to outside politics.

Maryland’s centralized system is designed under the assumption that Democrats will always control the state government, and therefore planning priorities won’t change very much from election to election. Were that actually the case, the system would work pretty well.

But recent history shows Maryland is not nearly so safe as Democrats might hope. With Larry Hogan’s election, two out of the last three Maryland governors have been Republicans. And they have different priorities.

Of course, it’s completely proper for political victors to have their own priorities. We live in a representative democracy, and we want it that way.

But shifting priorities are a big problem for any large infrastructure projects that take more than one governor’s time in office to complete.

It takes at least 10 years to plan and build something like a light rail line, or a new highway. If every new governor starts over, the project never gets done.

Thus, large infrastructure projects like the Purple Line, Baltimore’s light rail, and even highways like the ICC wallow in uncertainty for decades, shifting back and forth as one governor’s pet project and another governor’s whipping post.

Maryland’s spent literally half a century debating and re-debating whether or not to build the ICC highway.

While many states centralize their planning for highways, so much money automatically flows towards highway expansion that a lot of big road projects inevitably sail through without becoming political issues. Since transit rarely has dedicated funding for long term expansion, transit projects are more likely to become politicized.

And although this problem can happen anywhere, Maryland’s particular system centralizing transit planning under the governor’s office seems to make it par for the course.

When regional or local agencies control more of the planning, they’re less susceptible to the whims of any individual election.

For example on the southern side of the Potomac, where Virginia kept Silver Line planning alive through multiple Democrat and Republican governors, but only managed to actually build it after the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority took over ownership of the project from the state in 2007. After that, the state was involved but not the leader, making the project less of a target for governors or legislators.

Is there a best of both worlds?

The benefit to statewide planning is statewide resources. The Maryland Department of Transportation is much more willing to spend its own money on transit than almost any other state DOT.

While Fairfax County and MWAA had to increase local commercial property taxes and tolls in the Dulles Corridor to build the Silver Line, MDOT leadership meant Montgomery and Prince George’s weren’t supposed to need such schemes for the Purple Line.

Could we find a way to preserve access to the state’s financial resources without putting urban transportation projects at the mercy of voters on the Eastern Shore? Maybe.

Virginia offers a compelling model, with its regional planning agencies like the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority. NVTA makes decisions and receives funding at the metropolitan level, and is governed by a relatively stable board rather than one single politician.

Naturally the NVTA system has trade-offs too. For example, NVTA has independent funding streams but doesn’t get to allocate VDOT money. And NVTA is ultimately under jurisdiction of the Virginia General Assembly, which can impose its will any time.

No system is ever perfect, and Maryland wouldn’t have to copy Virginia directly. But something similar in concept might work, especially if it combined regional decision-making with state funding.

Don’t mistake Maryland’s problem as a criticism of planning in general

One common trope among some sprawl apologists and highway lobbyists is that central planning is inherently bad. For them, “central planning” is a code word that really means smart growth and transit planning in general.

Maryland’s reliance on statewide rather than regional-level planning does not prove those pundits right. Without government planning no large infrastructure projects would be possible at all.

Maryland has a specific problem with how it implements its planning, which leaders in the state can practically address without throwing the planning baby out with the bathwater.

Perhaps it’s time to begin that conversation.

Cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington. Cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.7 out of 5 based on 169 user reviews.

November 7th, 2014 | Permalink

Tags: government, lightrail, proposal, roads/cars, transportation

|

Media

Site

About BeyondDC

Archive 2003-06

Contact

Category Tags:

Partners

|

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.