|

Special Features

Image Libraries

|

|

Blog

Walkable City describes the benefits of urbanism, and proscribes how to make good urbanism happen. It’s a worthy read, for both newbies and hardened Jane Jacobs veterans.

I don’t read many mass market city planning books anymore, because so many of them say the same things. But when I heard one of the authors of Suburban Nation had his own book, I had to give it a shot. Suburban Nation is still the most eminently readable and easy to understand discussion of 20th Century suburbs, and why urban neighborhoods are better.

In some ways, Walkable City is like all those other books. It says mixed use and transit are good, wide highways and blank walls are bad. Most of us in the city planning world already know these things.

But Walkable City is worth reading, because Speck gathers a mountain of data supporting most of the arguments in contemporary urbanism, and then presents it in a convincing, methodological, and easy to read way. If you already know the basics, Walkable City is the most complete reference available.

And it does have new arguments. For example, Speck’s discussion of walkable architecture is intriguing, and explains in detail why it isn’t the ornament of historic buildings that makes them superior to most contemporary ones, but that they have layers of interesting things to look at, from different scales, and that walkers can interact with them in ways other than staring at a wall (even a decorated one).

Maybe I just like the book because I’m in it. Much to my surprise. I was reading it one day on the Metro and then, unexpectedly, on page 58, saw my own name, quoted regarded LEED architecture.

But perhaps the best thing I can say about Walkable City is this: After reading the first couple of chapters in a cafe, I went home, got a pen, and started over. Now my copy is covered with notes and squiggles from front to back.

Average Rating: 5 out of 5 based on 287 user reviews.

May 6th, 2013 | Permalink

Tags: people, urbandesign

|

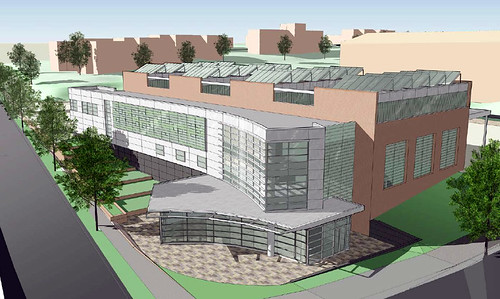

Rendering of potential H Street FBI building. Image from Arthur Cotton Moore via Washingtonian. |

As the FBI searches for a new headquarters location, most of the options have focused on the suburbs or Poplar Point, but Washingtonian reports on another proposal: Keep it downtown, at H Street and North Capitol Street, NW. But that location has serious downsides.

The proposal would repurpose the existing Government Printing Office buildings on North Capitol Street, and add a new extension to the west. The new building would be over 2 million square feet, and would cover multiple blocks from New Jersey Avenue to North Capitol.

Ideally an employer as large as the FBI should have its offices downtown, but the FBI isn’t just any employer. Its building is likely to be a security fortress, which means it won’t be very good for pedestrians, or have ground floor retail. H Street is an important pedestrian and retail spine. Giving up a long stretch of it to the FBI would be just as bad there as it is on E Street, where the FBI is a sidewalk dead zone.

Actually, a dead zone on H Street might be even worse. Walmart is building an urban format store directly across the street from the FBI proposal. And love Walmart or hate it, it’s going to be one of downtown’s biggest retail draws. That means this exact block of H Street is about to become one of the busiest retail main streets in the city. It should have retail on both sides.

One advantage of this FBI proposal is that the land is already owned by the government. That does mean it’s less likely to get retail on it, but putting the FBI building on it would cement that, literally.

There are other questions. DDOT’s proposed crosstown streetcar would run along H Street. The FBI has never weighed in on streetcars, but would they throw up security-related roadblocks? It’s unknown.

According to Washingtonian, the FBI would close G Street entirely to traffic. That further cripples the L’Enfant grid at a time when other projects are trying to restore the grid nearby. And would this forbid pedestrians and cyclists as well?

Finally, the existing GPO buildings are among Washington’s most prominent historic red brick buildings, and were designed by a prominent architect at the time. The FBI concept renderings show a courtyard in the middle of the GPO building, but aerials show no such courtyard currently exists. That suggests the buildings will have to be completely gutted to fit the FBI. Is that a worthy tradeoff?

Any proposal that keeps the FBI downtown merits serious consideration, but given the FBI’s security requirements, and given the potential for this location to be redeveloped with something even better, it may be preferable to let the FBI go. Putting the FBI on this block might be better than having it remain a parking lot, but almost any other building would be more ideal.

Cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington. Cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.8 out of 5 based on 264 user reviews.

April 4th, 2013 | Permalink

Tags: development, government, urbandesign

|

11th and V poptop. |

This 5 story pop-up rowhouse at 11th and V, NW has gotten a lot of negative press. DCist and Popville had nothing kind to say about it. And while it’s undeniably a silly-looking thing, it’s not actually bad. In fact, from an urbanist perspective, it’s good for the city.

First, a bigger building will allow more people to live in a core city neighborhood. That will help the neighborhood support more stores and services, and reduce car traffic everywhere. Density in the core of the city is a good thing, and a 5 story building is a very reasonable amount of density.

Second, this preserves the narrow lot pattern of its block, versus having one developer buy up multiple row houses and then put in a much wider building.

All other things being equal, a street with several narrow buildings is preferable to a street with a single long building of the same square footage. A streetscape with constantly changing narrow buildings is more interesting to look at than one with a single long building. Narrower buildings are also more likely to be owned by small local property owners, instead of big development chains.

Yes, this property looks silly now. But think about the future. Assuming we can’t (and don’t want to) freeze the city in time, densifying infill on small properties is exactly the kind of development we want. If it’s all eventually going to be 5 stories anyway, it’s better that this block redevelop property-by-property than all once.

Pop-ups are the first step towards this in Amsterdam, which really isn’t such a bad thing.

Amsterdam. Photo by Jim Nix / Nomadic Pursuits on Flickr.

Will this particular building look as good as that picture? It’s hard to tell at this point. It might, but it could just as easily become the ugliest building in DC. Buildings that size aren’t inherently pretty or ugly. There are lots of good ones, and lots of bad ones. What it looks like is not ultimately the same issue as its mass and scale.

The point is, narrow 5 story buildings are a great physical form for city streets. That’s the form of some of the best parts of Paris, London, and New York. Although this will look weird with 2 story neighbors, it pushes the evolution of the block in a good direction.

Cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington. Cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.9 out of 5 based on 236 user reviews.

April 2nd, 2013 | Permalink

Tags: architecture, development, urbandesign

|

Development like this is impossible with parking minimums. |

Parking minimums don’t just affect parking. They have a huge impact on the overall scale of buildings. Developers that have to include off-street parking have to build bigger and bulkier buildings in order to make their projects work.

It’s true that parking minimums encourage more driving, but the impacts on urban design and architecture may be even more important. The problem is that parking lots take up a lot of space, which makes development of small properties harder.

As a result, developers faced with parking minimums always try to build on the largest piece of land possible.

So if you like old style main streets, parking minimums are the enemy.

In places without parking minimums it’s more practical to build charming narrow buildings, like those that populate historic main streets all over the country. But where parking minimums exist, developers need larger properties big enough to fit parking lots.

Take a look at the buildings in these two pictures. They’re ostensibly similar. Both are 3 stories with a 4th floor attic. Both are primarily brick. Both have shops on the ground level, with other uses above. The key difference is that the left picture is a single building built by a single developer, while the right picture shows a block of narrow buildings on individual properties.

University Drive, Fairfax.

Image from Google. |

King Street, Alexandria.

Image from BeyondDC. |

Which one do you like better? Most people prefer the buildings in the right picture, because they’re built at a more human scale. Even though the building on the left is about the same height, it seems like a hulking monster because it’s so long.

One of the big reasons it’s so long: Parking.

Parking lots take up so much space and push developers towards larger buildings because parking lots aren’t just parking spaces. They’re really entire streets. Since you can’t get to a parking space unless it’s got a driving lane next to it, every row of parking spaces has to have an entire street built in front of it.

Unfortunately, it’s geometrically impossible to fit a two-way driving lane and a bunch of parking spaces behind a main street style 25-foot-wide building. Thus, developers need bigger properties, and old style main streets are essentially illegal to build.

Parking garages and underground parking are even worse. They don’t just need driving lanes, they need ramps too, not to mention elevators, stairs, and air ducts. So anyone who wants to build something that requires structured parking needs even more land.

This is one of the biggest reasons why contemporary development happens at the scale that it does. There are other reasons too, but this is a key one. In order to meet parking requirements imposed by city governments, developers have to scale-up their buildings to fit parking lots. In turn, those 19th Century main streets that everyone loves so much are effectively impractical and illegal to build.

Average Rating: 4.5 out of 5 based on 223 user reviews.

January 11th, 2013 | Permalink

Tags: architecture, roads/cars, transportation, urbandesign

|

Rosslyn, once again eligible for DoD offices. |

On a day when Maryland released renderings of the Purple Line subway in Bethesda, and Arlington got specific on streetcar vehicles, the biggest urbanist news is probably that the Department of Defense has relaxed security rules that effectively outlawed using urban buildings for DoD offices.

After 9/11 the Pentagon established strict security standards for DoD offices. Among other things, those standards required large setbacks from the street, which meant that offices couldn’t locate in the most central urban areas, or in pedestrian-oriented buildings. This pushed a lot of federal workers out of Metro-accessible offices in places like Rosslyn and Crystal City out to more suburban locations.

The new rules, which were announced on December 7 but didn’t hit the public news until yesterday, relax the rules so that DoD offices only have to comply with the same design standards as federal office buildings leased by civilian agencies. This means they can once again locate in urban buildings.

Not only does this eliminate a major advantage that suburban office centers had over urban ones, it also reduces the pressure to build bad suburban buildings in urban places that should be walkable.

Good news.

Average Rating: 4.4 out of 5 based on 299 user reviews.

December 20th, 2012 | Permalink

Tags: government, lightrail, streetcar, transportation, urbandesign

|

La Pedrera, Barcelona, product of height & form regulations even more strict than DC’s. Photo by Effervescing Elephant on flickr. |

There are plenty of good arguments for why DC’s height limit should be tweaked, but one that rings completely hollow is the claim it’s responsible for a bland, boxy streetscape, and DC would be more beautiful if only architects weren’t so constrained.

Any architect who says they can’t design a good or creative building under DC’s height limit is, to be blunt, a bad architect.

Brent Toderian at The Atlantic Cities discusses this same point (paraphrased):

Whenever I hear North American architects complaining that regulations or requirements “constrain architectural creativity, ” I think of Barcelona’s Passeig de Gracia boulevard and Paris’ Avenue des Champs-Elysees, which strictly regulate their buildings’ height, but still allow for great architectural beauty and nuance.

The easiest example is Gaudi’s La Pedrera, which acts as a “typical” corner building within Barcelona’s brilliant block plan that regulates height and form – and yet there’s nothing typical about Gaudi’s design.

It’s true that every city has rules that are both smart and dumb. Great architects know that genius often arises out of constraint.

It is true that DC’s regulations result in buildings with a boxy shape, but weird shapes are not the only way to make a building interesting, and anyone who thinks otherwise is intellectually bankrupt. No one would argue that K Street looks like Champs-Elysees, but that’s not because of the height limit. That’s because K Street’s buildings don’t have enough decoration.

Beautiful buildings can absolutely be produced within the context of DC’s height and form regulations, but to do so requires architects to step outside their 20th Century dogma that declares ornament to be the enemy. To do so requires architects to design something other than blank glass facades.

La Pedrera is an extreme example, handy for illustrating the point, but one does not need to go to Barcelona to see this fact in practice. Here are three relatively recent DC buildings that somehow have managed to be interesting, despite having to be designed within the context of the height limit.

You may or may not like these buildings, but they’re objectively not bland.

But that’s not the only reason the “don’t constrain us” argument is so uncompelling. Another reason is that there is already a mechanism in place to allow height limit exceptions for primarily aesthetic architectural features. The prime example is the One Franklin Square office building, which received permission to break the height limit for a pair of decorative twin spires.

One Franklin Square.

So either way you look at it, the claim that DC’s height limit is responsible for bland architecture is simply not true. The world is full of examples of beautiful buildings produced in environments that constrained their size and shape, and even if it weren’t, DC’s regulations don’t actually constrain architects very severely.

Let’s continue to talk about the economic, social, and urban design issues facing the height limit question, but let’s put this one to bed. The height limit is not responsible for bland architecture in DC. At most, it’s a convenient excuse.

Average Rating: 4.5 out of 5 based on 151 user reviews.

December 3rd, 2012 | Permalink

Tags: architecture, urbandesign

|

Arlington’s Orange Line corridor. Home to tall buildings, and good for the region. |

The question over whether or not to raise DC’s height limit has come up periodically for several years, but gained new traction earlier this month when some members of Congress asked for a study about modifying the height limit legislation. With the possibility of actual change looming, more and more people are weighing in.

Most height limit opponents have so far based their position on the argument that taller buildings downtown would be more economically efficient, and that allowing some offices to be located outside downtown is costing DC a lot of money.

The latest to do so is David Schleicher at The Atlantic Cities, who opposes the height limit and poses a series of questions to supporters.

Having long advocated for raising the limit strategically, both downtown and in surrounding areas, I cannot be characterized as a height limit supporter. But I also think that the economic arguments put forth by the loudest height limit opponents, including Schleicher, are too narrow and miss important considerations.

> Continue reading

Average Rating: 4.8 out of 5 based on 159 user reviews.

November 28th, 2012 | Permalink

Tags: question, urbandesign

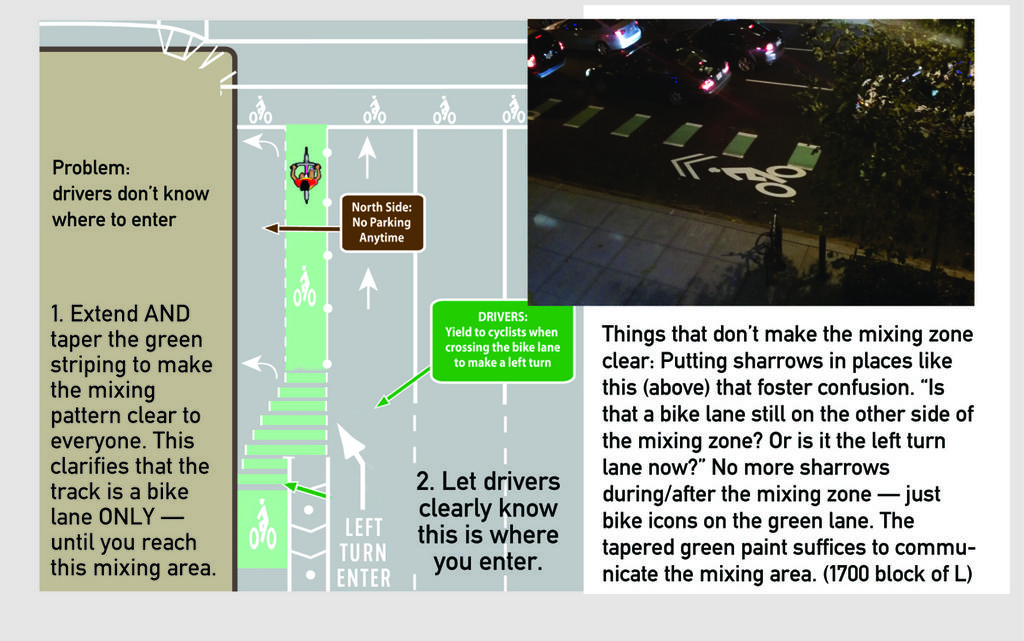

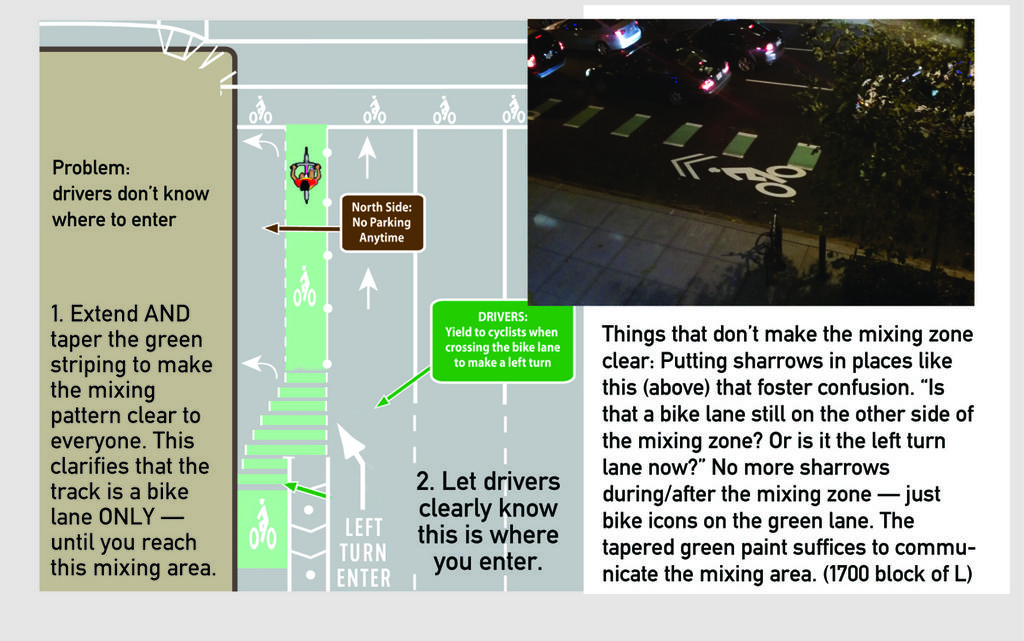

The L Street cycle track is open, but the pavement markings continue to be confusing for some people. Car drivers planning to turn left off of L Street often don’t understand how to cross the cycle track into the turn lane, and instead stay in the travel lane only to cross in front of the bike lane at the intersection.

In response, twitter user @whiteknuckled proposes this modified painting scheme:

I am always in favor of more green paint on bike lanes, and this idea is no exception. However, the real key to solving this problem is the arrows on each car lane, especially the “left turn enter” one, which indicates to drivers where to cross over the bike lane. That’s the awkward movement, so that’s what needs to be clarified.

In a twitter response, DDOT notes that bikes turning left are also supposed to use the left turn lane, which is why they used sharrow markings in that area. But DDOT’s twitter rep also promised to pass along this idea to the bike team for their thoughts.

Cycle tracks are still a pretty new thing in the United States, so it’s natural that designers need to experiment a little with different options. DDOT deserves enormous praise for being on the very cutting edge of this field.

Other DOTs might have waited years until all these design questions are answered and there’s an adopted nationwide standard for every conceivable layout, but DC needs better bikeways now, and DDOT is doing its best to deliver. That’s great.

But it also means they may have to adjust the lanes as we learn how cyclists and drivers interact with it in the real world.

Ideally DDOT could apply both the turn markings and green paint section, as whiteknuckled suggests, but at a minimum, “left turn enter” markings for cars could make a big difference.

Cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington. Cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.5 out of 5 based on 261 user reviews.

November 14th, 2012 | Permalink

Tags: bike, roads/cars, transportation, urbandesign

In recent years there has been a lot of discussion about raising DC’s building height limit. Today that discussion moved into the realm of official policy-making, as Congress announced it will study the issue. Any change to the height limit would need Congressional sign-off.

In general I think the height limit should be raised subtly, in key places for key reasons, based on careful planning. I’m in favor of using taller buildings to incentivize more development where we want it, but don’t think it would be wise to simply eliminate the limit completely.

That’s sounds simple, but the issue is pretty complex. Here are some key points, with links to more expanded discussion:

- Uptowns: Raising the limit in places like Anacostia and Tenleytown would encourage them to develop as uptowns, like Arlington and Bethesda.

- Negatives: Raising the limit in downtown DC would increase pressure to tear down historic buildings, and decrease the pressure to fill in parking lots and other underused properties.

- Tall =/= dense: Counterintuitively, midrise development is often more dense than skyscrapers.

- Residential bonus: Giving developers a height bonus in exchange for building apartments instead of office would increase the vitality of downtown.

- Do it, but carefully: We should raise the height limit with a scalpel, not a hatchet.

- Trade-offs: Despite economic advantages, there are non-economic trade-offs about raising the height limit that we can’t ignore.

- Be practical:: We should consider how to realistically improve the city’s regulations, not stake out dogmatic extremes.

Average Rating: 4.9 out of 5 based on 170 user reviews.

November 8th, 2012 | Permalink

Tags: government, land use, master planning, preservation, urbandesign

David Alpert contributed to this article.

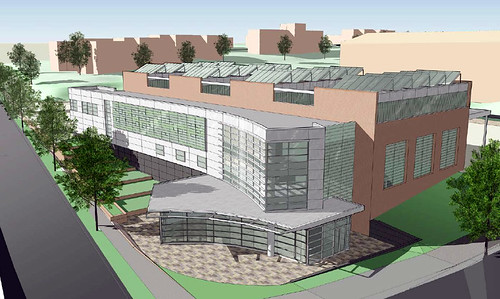

Last night, DDOT released renderings of its design for the proposed Spingarn streetcar barn. The proposal is a passable building, but the design is likely to disappoint residents who’d been expecting great architecture.

Streetcar barn design. Image from DDOT.

DDOT originally wanted to locate the maintenance facility for its H Street streetcar under the Hopscotch Bridge, near Union Station. That proved impossible, so DDOT switched its plans to the most practical alternate site: the Spingarn High School campus.

Though the design lacks the ornament and detail of DC’s historic streetcar barns, it is typical of contemporary institutional architecture, which is a step up from the bare bones necessary for industrial buildings.

In fact, this design looks very much like a modern school. If DCPS were building a new education building on the same site, it would probably look pretty similar, at least as seen from Benning Road. Adjacent residents likely won’t feel they are living right next to an industrial facility.

However, it’s not the sort of civic architecture that leaves much of an impression. Many cities’ new car barns aren’t good civic architecture either, but DDOT has been suggesting that this building would be better than merely okay.

The design guidelines call for “the highest aesthetic quality, ” and there’s a lot that could be done to improve this building. Some of DC’s new libraries show how civic buildings can indeed be exemplary.

Image from DDOT.

Some changes can improve the design

The primary purpose of the barn will be to park and maintain streetcars, but it will also include a training center, offices, and employee prep areas. One nice touch in the building design is that those non-industrial uses line Benning Road, so that from the sidewalk the upper floors of the building look like a school or office instead of a warehouse. Unfortunately, the ground floor is bare, so the illusion is incomplete.

Design guidelines call for public art to be included, and these renderings don’t appear to have any. Perhaps that first floor wall would be a good location for a mural.

Another disappointing facet is the location of the public entry on the side rather than the front or corner, where most would expect it. The reason appears to be that the interior layout puts offices and a copy room at the street corner, pushing the entry back a few feet onto 26th Street. This seems needlessly confusing, and prioritizes the wrong function.

The Historic Preservation Review Board discussed the project on November 1. Their comments begin at the 2:00:00 mark on the archived video, and focus on whether or not a modern-looking building is appropriate, and whether the plan could be reduced to have less visual impact. They did not take any vote at that meeting, but will do so when they consider the landmark application for Spingarn later this month.

The streetcar project is important, and this car barn is good enough to not delay the project. But while this is pretty good for a building that’s basically a garage, it could be much better. A car barn on the Spingarn campus makes sense, and this one isn’t terrible, but residents asked for an exemplary building, and DDOT said it could deliver.

DDOT also needs to be more open to the public about its planning for the streetcar. These renderings came out at 4:30 pm the evening before a Presidential election. Given the concern neighbors have about the planning process for the car barn, DDOT must make every attempt to be as open as possible.

It’s not necessary to completely start over, but some improvements do seem in order. Likewise, as DDOT starts to plan for future car barns in other neighborhoods, they shouldn’t settle for “just okay.”

Cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington. Cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.5 out of 5 based on 261 user reviews.

November 6th, 2012 | Permalink

Tags: architecture, development, preservation, streetcar, transportation, urbandesign

|

Media

Site

About BeyondDC

Archive 2003-06

Contact

Category Tags:

Partners

|