|

Special Features

Image Libraries

|

|

Blog

There are more than 20 separate bus agencies in the Washington area. Why not run them all as part of WMATA? Some run outside WMATA’s geography, but the bigger reason is money: It costs less to run a local bus than a WMATA bus, translating to better service for less money on local lines.

With a few exceptions, essentially every county-level local government in the Washington region runs its own bus system, on top of WMATA’s Metrobus. DC has Circulator, Montgomery County has Ride-On, Alexandria has DASH, etc ad nauseam. There are more than 20 in the region, not even including myriad private commuter buses, destination-specific shuttles, and app-based startups.

Our region is a smorgasbord of overlaying transit networks, with little in common except, thankfully, the Smartrip card.

Why?

Three reasons, but mostly it’s all about money

Some of the non-WMATA bus systems can’t be part of Metro simply because buses go to places that aren’t part of the WMATA geography. Since Prince William County is outside WMATA’s service area, Prince William County needs its own system. Thus, OmniRide is born. Hypothetically WMATA could expand its boundaries, but at some point 20 or 40 or 60 miles out from DC, that stops making sense.

Another reason for the transit hodgepodge is control. Locals obviously have more direct control over local systems. That’s an incentive to manage buses close to home.

But the biggest reason is money. Specifically, operating costs.

To calculate how much it costs to operate a bus line, transit agencies use a formula called “cost per revenue hour.” That means, simply, how much it costs to keep a bus in service and carrying passengers for one hour. It includes the cost of the driver’s salary, fuel for the bus, and other back-end administrative costs.

Here are the costs per hour for some of the DC-region’s bus systems, according to VDOT:

- WMATA Metrobus: $142/hour

- Fairfax County Connector: $104/hour

- OmniRide: $133/hour

- Arlington County ART: $72/hour

Not only is WMATA the highest, it’s much higher than other local buses like Fairfax Connector and ART. OmniRide is nearly as high because long-distance commuter buses are generally more expensive to operate than local lines, but even it’s less than Metrobus.

This means the local systems can either run the same quality service as WMATA for less cost, or they can run more buses more often for the same cost.

At the extreme end of the scale, Arlington can run 2 ART buses for every 1 Metrobus, and spend the same amount of money.

In those terms, it’s no wonder counties are increasingly pumping more money into local buses. Where the difference is extreme, like in Arlington, officials are channeling the vast majority growth into local buses instead of WMATA ones, and even converting Metrobus lines to local lines.

Why is Metrobus so expensive to run?

Partly, Metrobus is expensive because longer bus lines are more expensive to run than shorter ones, so locals can siphon off the short intra-jurisdiction lines for themselves and leave the longer multi-jurisdiction ones to WMATA.

Another reason is labor. WMATA has a strong union, which drives up wages. The local systems have unions too, but they’re smaller and balkanized, and thus have less leverage.

Finally, a major part of the difference is simply accounting. WMATA’s operating figures include back-end administrative costs like the WMATA police force, plus capital costs like new Metro bus yards, whereas local services don’t count those costs as part of transit operating.

Montgomery County has a police department of course, and bus planners, and its own bus yards, but they’re funded separately and thus not included in Ride-On’s operating costs.

So part of the difference is real and part is imaginary. It doesn’t actually cost twice as much to run a Metrobus as an ART bus. But for local transit officials trying to put out the best service they can under constant budget constraints, all the differences matter.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.7 out of 5 based on 292 user reviews.

February 22nd, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: bus, government, transportation

DC Mayor Muriel Bowser just announced the H Street streetcar will officially open to passengers on Saturday, February 27. Of this year. Hallelujah!

Mayor Bowser’s announcement should mean the DC fire department has certified the streetcar as safe to run and submitted its paperwork to the federal government, thus accomplishing the last step before the streetcar can open. With that done, it’s ready to carry passengers.

The opening party and first passenger-carrying run will take place at 10:00 am on Saturday, February 27, at the corner of H Street and 13th Street NE.

After that, streetcars will run between Union Station and Oklahoma Avenue every 15 minutes the rest of the day. Rides will be free for everyone for the first few months.

The streetcar will close again Sunday the 28th; for now it’s only scheduled to run six days per week. But passengers will be able to pick it up again on Monday the 29th, and every day thereafter except Sundays.

Many of us will be there to enjoy the festivities, and we’ll try to all meet up to make a GGWash contingent. Join us if you can! Or ride the streetcar to our 8th birthday party on March 8. Or both!

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.4 out of 5 based on 229 user reviews.

February 18th, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: events, streetcar, transportation

Say goodbye to Metro railcar number 1013. Along with other 1973-vintage 1000-series railcars, it’s headed to the scrapyard. More aren’t far behind.

Metro railcar 1013 at a scrap yard in Baltimore. Photo by MJofLakeland1 on Flickr.

As new 7000-series railcars enter Metro service, WMATA is now beginning to retire its oldest railcars. So far the agency has scrapped four cars, with more scheduled to head out the door beginning this March.

In the past if WMATA had to permanently take a railcar out of service, they’d either keep it for parts or backup, or it would end up in any number of weird places. That happened rarely for most of WMATA’s first four decades.

That’s now changing. With the impending mass retirement of 400 decades-old 1000-and-4000-series cars, WMATA needed a process to handle getting rid of so many cars at once.

Since signing a scrapping contract late last year they now have that process, and railcars can begin to head to the scrapyard.

When that happens, workers truck the old railcar to United Iron & Metal in Southwest Baltimore, where they strip it of valuable materials.

It’s an inglorious end for these old workhorses, but I’m not too sorry to see them go; those new car replacements are nice.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.9 out of 5 based on 223 user reviews.

February 18th, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: metrorail, transportation

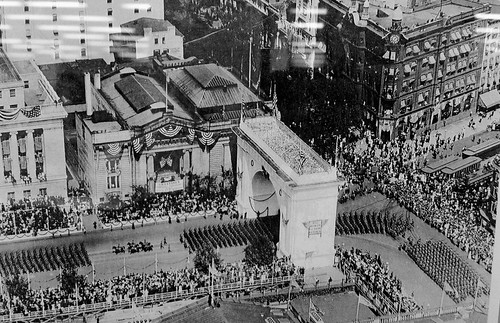

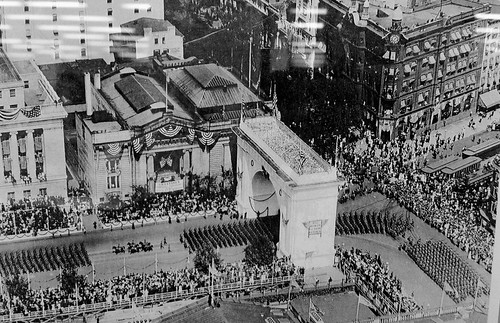

Paris’s Arc de Triomphe is world famous, but did you know DC once had its own version?

Photo from the DC Public Library.

The Washington, DC Victory Arch sat on Pennsylvania Avenue, at the corner of New York Avenue and 15th Street NW.

It was a temporary structure built to commemorate the end of World War I. This photo, from 1919, shows the US Army on parade following the end of the war. Presumably the arch was made of plaster, like the White City of Chicago, and thus never intended to be permanent.

Here’s another view, showing the arch from ground level.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.8 out of 5 based on 234 user reviews.

February 11th, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: architecture, fun, history

Once upon a time, having a walkable, urban city was a niche idea in our region, one special interest among many. Today it’s a mainstream discussion topic all over the region’s cafés and living rooms.

Greater Greater Washington helped make that happen, and it relies on reader donations to survive. Please consider giving GGW a donation, so it can keep fighting the good fight.

Read more about why you should give to GGW, or skip the pitch and donate now!

Average Rating: 5 out of 5 based on 277 user reviews.

February 10th, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: site

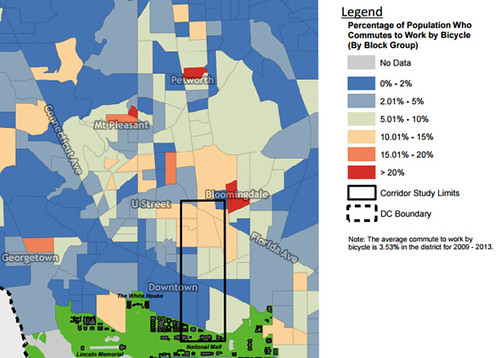

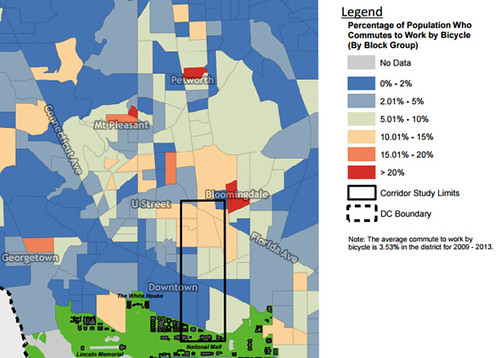

Over 20% of commuters in Bloomingdale, Mount Pleasant, and Petworth get to work each day primarily using a bicycle. That doesn’t even include people who use bikes to reach Metro.

Bike mode share in central DC. Image from DDOT.

This fascinating map is part of the background data DDOT is preparing to study a possible protected bikeway on or around 6th Street NW.

It shows how hugely popular bicycling can be as a mode of transportation, even in the United States. What’s more, this data actually undercounts bicycle commuters by quite a lot.

It’s originally from the US Census’ American Community Survey, which only counts the mode someone uses for the longest segment of their commute. People who bicycle a short distance to reach a Metro station, then ride Metro for the rest of their commute, count as transit riders rather than bicyclists.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.9 out of 5 based on 298 user reviews.

February 8th, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: bike, maps, transportation

Milan, Italy’s second largest city, has a neighborhood named “Washington.” Its main street: Via Giorgio Washington.

Washington, Milan. Map by Google.

Washington Quartieri is about a mile from the center of Milan, outside its historic Renaissance core but very much in the midst of town. It looks like this:

Via Giorgio Washington. Photo by Google.

Milan isn’t the only European city to honor Washington. At least one other, Paris, has a short Washington street near Champs-Élysées.

Both Milan’s Via Giorgio Washington and Paris’ Rue Washington are more likely named for George Washington himself than for our fair District of Columbia. But still, it’s interesting to look at a map of a European city and see “Washington” in bold letters.

What other foreign cities have streets or neighborhoods named Washington?

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.4 out of 5 based on 151 user reviews.

February 3rd, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: fun

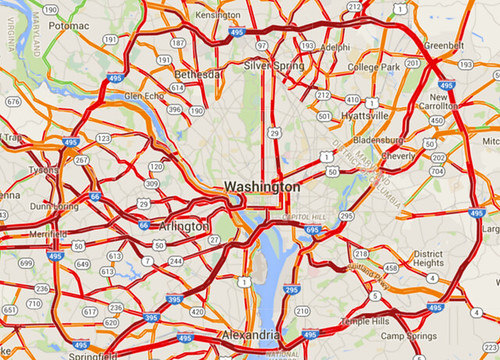

A lot of people had awful commutes last night, thanks to snow. And a lot of people had fine ones. One explanation for the difference: Suburban roads are far more susceptible to catastrophic breakdown than urban street grids.

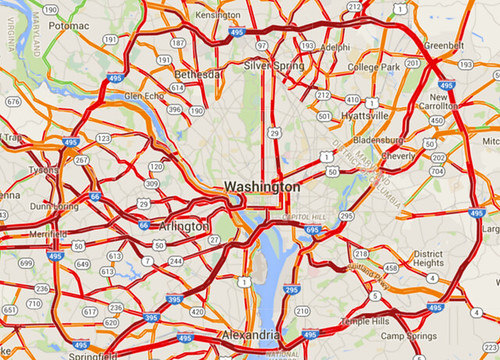

Traffic congestion on snow night. Image from Google.

Snow storms like last night’s highlight how easy it is to completely shut down suburban-style transportation systems. And conversely, how comparatively resilient are more urban systems.

Cities beat suburban areas on snow resiliency in two big ways: Multimodalism and network connectivity.

First and foremost, with transit, walking, and biking more convenient options, cities are simply much less reliant on having clear roads. Metrorail worked like a dream yesterday, and pedestrians had a lovely commute.

It simply didn’t matter how bad the roads got for a significant percentage of DC’s travelers, because they simply weren’t on the roads while they traveled.

Don’t put all your eggs in one basket

But that’s not all. Even for car drivers, urban street grids are more resilient than road systems focused around large highways, because of how they’re laid out.

The great thing about interconnected grids is that if one street becomes blocked, there’s another perfectly good street one block over. And another one block down.

If a wrecked car or fallen tree or whatever blocks the street you’re on, you just take a different street. There might be some additional turns involved; it might not be quite as direct. But for the most part 28th Street isn’t all the different from 29th Street.

Contrast that with suburban-style systems where all traffic in a particular area funnels onto one big highway. If that one highway becomes impassible, everyone in the area is stuck. Or, at best, they have to drive miles out of their way to find the next big highway.

This illustration shows how that works. If the “Collector Road” gets jammed, people in the top half of the image can still move around. People on the bottom half can’t.

Suburban-style roads vs urban street grid. Image from USDOT.

That’s part of what happened last night. There were a lot of crashes. If they happened on arterial highways with no parallel roads, which a lot of them did, that road would succumb to gridlock.

Urban places aren’t immune, but they’re better off

To be sure, this storm was bad for roads all over the region.

Streets in Northwest DC were just as dangerous as those elsewhere, and DC’s plowing response was bad. And buses were every bit as stuck in it as cars.

But there’s no doubt that people who could travel via Metro or foot had a much better time, and there’s no doubt that drivers who could use parallel streets were able to bypass some of the congestion on arterials.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.9 out of 5 based on 275 user reviews.

January 21st, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: environment, master planning, roads/cars, transportation

What do you do if you have active freight rail tracks running down the middle of a downtown street? Add bike lanes, of course!

East Avenue, Clearwater, FL.

This is East Avenue in downtown Clearwater, Florida. It’s one of America’s most unusually multimodal streets.

On the left: A normal one-way general purpose lane with normal car traffic. In the middle: Freight rail tracks. On the right: A major regional two-way bikeway, the Pinellas Trail. What could go wrong?

Actually, it’s not as dangerous as it looks. Freight traffic on those tracks is relatively light, and extremely slow-moving. The train in this photo was moving maybe five miles per hour. And unlike cars, trains don’t suddenly change lanes. There’s zero danger of a CSX right hook.

In fact, the rail tracks are effectively a buffer between the bikeway and car lane. They make a bigger buffer than normal buffered bike lanes get. In a weird way, the tracks are a sort of protection.

So it’s totally bonkers. But maybe it works.

What do you think?

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 4.8 out of 5 based on 174 user reviews.

January 13th, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: bike, fun, transportation, urbandesign

According to the California housing champion who’s suing communities that don’t allow enough new development, not building needed density is morally equivalent to tearing down people’s houses.

Photo by .Martin. on Flickr.

Sonja Trauss, founder of the SF Bay Area Renters’ Federation sums up the housing problem affecting nearly every growing American city today:

“Most people would be very uncomfortable tearing down 315 houses. But they don’t have a similar objection to never building them in the first place, even though I feel they’re morally equivalent. Those people show up anyway. They get born anyway. They get a job in the area anyway. What do they do? They live in an overcrowded situation, they pay too much rent, they have a commute that’s too long. Or maybe they outbid someone else, and someone else is displaced.”

Trauss hits the key points: The population is growing, and people have to live somewhere. If we refuse to allow them a place to live, that’s just like tearing down someone’s home.

Someone else is displaced

Trauss’ last sentence is particularly important. It explains how the victims of inadequate housing often are not even part of the discussion. She says “Or maybe [home buyers] outbid someone else, and someone else is displaced.”

Here’s how that works: One common argument among anti-development activists is that new development only benefits the wealthy people who can afford new homes. That’s wrong. It’s never the wealthy who are squeezed out by a lack of housing. Affluent people have options; they simply spend their money on the next best thing. Whenever there’s not enough of anything to meet demand, it’s the bottom of the market that ultimately loses out.

Stopping or reducing the density of any individual development doesn’t stop displacement or gentrification. It merely moves it, forcing some other person to live with its consequences.

Every time anti-development activists in Dupont or Georgetown or Capitol Hill reduce the density of a construction project, they take away a less-affluent person’s home East of the River, or in Maryland, or somewhere else. The wealthy person who would have lived in Capitol Hill instead moves to Kingman Park, the middle class person who would have lived in that Kingman Park home instead moves to Carver Langston, and the long-time renter in Carver Langston gets screwed.

As long as the population is growing, the only ultimate region-wide solution is to enact laws that allow enough development to accommodate demand.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington. Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Average Rating: 5 out of 5 based on 166 user reviews.

January 5th, 2016 | Permalink

Tags: development, economy, environment, law, preservation

|

Media

Site

About BeyondDC

Archive 2003-06

Contact

Category Tags:

Partners

|

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.

Comment on this at the version cross-posted to Greater Greater Washington.